January 27, 2010

Stacey Mason/Mark Bernstein

Those who do know their history are amused at how often it repeats itself anyway. Our current technological revolution is not the first time art and technology have come together in new and exciting way. In 1944, Popular Photography magazine gathered various people—from experts to soldiers— and their thoughts on the future of photography. Much of it sounds strikingly familiar.

At present photographers do not know their medium enough to use their medium. A writer knows how to write and a composer knows theory of music so that they can extend their arts beyond purely technical elements. But in the future the technique of photography will be so simplified and so widely taught and understood that the illiterate per son will be the one who is not a photographer. Then, with mastery of the purely physical features of photography at his command, the photographer can go as far as his will of expression and his imagination will lead him. Even so, there will be good, better, and best.

With interviews from Paul Strand, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Berenice Abbott among others. Abbott’s name is misspelled but her technical criticism is terrific.

Thanks, Jason Kottke!

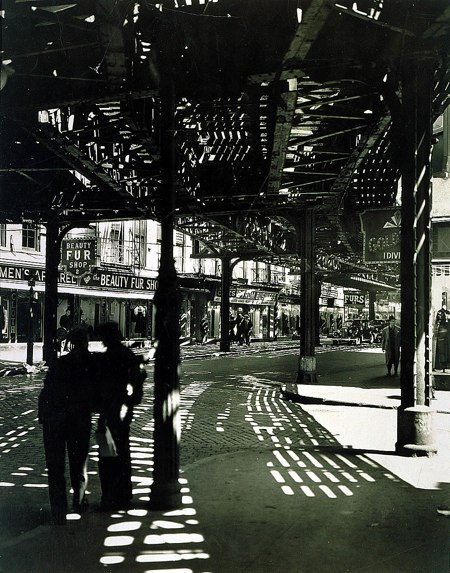

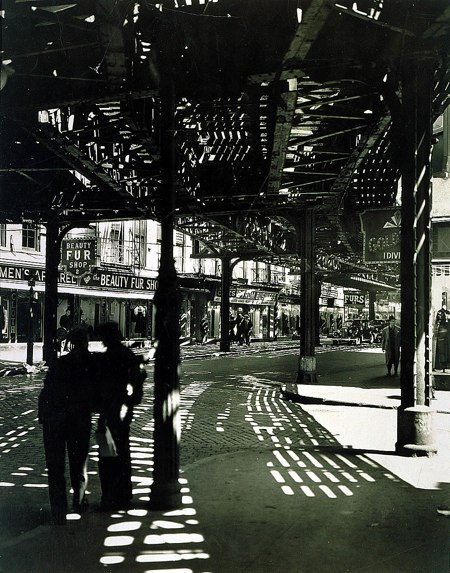

Berenicew Abbott, ‘El’ Second and Third Avenue Lines; Bowery and Division Street, Manhattan, 1936.Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of George McNeil

Jill Walker Rettberg brings news of a large European project aimed at exploring how creative communities for electronic literature develop and interact. The project will be led by Scott Rettberg, and includes researchers from seven universities across Europe.

Susan Gibb writes of her experiences with hypertext style

While I’ve sort of been accused of using an old fashioned form of hypertext narrative–and this may be true since I’m a bit behind the times learning on my own–I’m still very much aware of the fact that folks need to be eased into the concept of hypertext story.

Text-only hypertexts may not take advantage of graphics, video, and audio, but when did having all of these things together become a requirement for literature? To ask this is to require a painter to use every color of the spectrum at once.

One of the joys of reading is being able to imagine things exactly how we want them. Images can take this away from a reader.

As for folks needing to be “eased into” hypertext, I think this is becoming less true as time goes on. Weblogs already combine text, links, and other media in ways that make sense to us. I recently showed Morpheus Biblionaut to someone who had never seen a hypertext before, and she had no problem understanding what was going on.

January 25, 2010

Stacey Mason/Mark Bernstein

Hypertext pioneer Cathy Marshall has just written Reading and Writing the Electronic Book. Marshall offers a brief history of electronic books, and focuses on what facets of reading eBooks inherit from print, how they are written and read, and how they are presented, and what they do to advance the future of literature. In contrast to much of what’s appeared to date, Marshall doesn’t base her opinions of books on received wisdom, nostalgia, or press releases, and this book’s explanation of how we can study actual readers is at once rigorous and accessible. Based on extensive research and thoughtful consideration, this volume is clearly the authoritative source on new ways of reading and new reading tools.

Taking Video Games Seriously is a discussion panel which will be held Monday January 25th from 6:30 pm in Westminster Hall in London. The panel will address how we should be looking at gaming and virtual worlds as a medium.

Leading the discussion will be:

- Tom Chatfield, senior editor at Prospect magazine, and author of Fun Inc, a major new book on the social importance of video games, published by Virgin Books on 14th January.

- Philip Oliver, CEO of Blitz Games, one of Britain’s largest independent games developers, and one of its most radical in pursuing the serious and innovative uses of games. With his brother, Philip is one of the founding fathers of the British games industry.

- Sam Leith is a cultural critic and author, and columnist for The Guardian, The Evening Standard and Prospect. A previous books editor at the Daily Telegraph, he has a particular interest in popular culture and emerging technologies, and writes regularly on video games.

If you are interested in attending, please contact Clair Pilsbury at pilsburyc@parliament.uk

BBC Audio has released Neil Gaiman’s Twitterfiction, “Hearts, Keys, and Puppetry.” The story is splendidly narrated by Katherine Kellgren, bringing the characters and action to life. (Here’s a Mark Bernstein review of another Kellgren audiobook.)

I have to admit, I was surprised at how good this was. The re-mediation is a suprise, moving from Twitter to voice is not an obvious choice. I expected to hear many different voices pulling the narrative in different directions; I expected the sentences to feel short and staccato. I expected to be driven to distracted. And I didn’t realize I expected any of this until I found that it wasn’t there. The story is immersive, with much credit given to Kellgren’s narratiom. There were a few moments which would occasionally remind me that the work was written over Twitter, with sentences like “Then Sam couldn’t believe what happened next.” But the story is fun, and it made my long and chilly commute much more enjoyable.

Sweet Agatha is a mystery narrative-building game by Kevin Allen Jr. that allows players to put together the mystery of a girl who vanished. It plays like a cross between a tabletop role playing game and a campfire story session. The game calls for two players. One player reads through an included booklet—her investigative journal—which includes cut-out clue tiles. Another player, The Truth, controls the clues, revealing them during dramatically important points in the story. The Reader and The Truth go back and forth to build the story of Agatha’s disappearance.

The very well-written booklet creates a sense of eerie mystery while leaving the scenarios open-ended enough to allow for creative input from both the Reader and The Truth. The images are haunting, and serve as great points of departure for the imagination.

This game would be a great exercise for writers looking to test their narrative development skills, or anyone looking to spend an afternoon building an interesting story.

January 15, 2010

Samantha Rose Panepinto

Michael Joyce’s “Twelve Blue”, a hypertext fiction by the author of afternoon: a story, explores the duality and the flow of life not only through the well-crafted segments of text but through its very structure.

Joyce begins one section by announcing there are “many ways to go over Niagara Falls”, illustrating a central concept of the story: that there are often many different ways to get to the same place. This idea applies to life in general, as Joyce elaborates through descriptions of maze-like roadways (all leading to Route 9), the motif of flowing water and a dose of religious skepticism – likening the mind of god, at one point, to the swirling mind of a drowning boy. Story segments comment on the scant control we have over our lives, not due to some divine plan but to life’s randomness and natural gravitations between certain people or things.

This interpretation is paralleled in the way the hypertext is set up: there are many ways to click through the links, thus giving the reader the illusion of choice, but there are very few options once a number is chosen at the beginning. We may take many different paths to reach conclusions, but we’re all reading the same story.

The narrative often splits or flows back, much like the rivers Joyce discusses. Points of interest for him are the brief moment a current flows in two distinct directions and the feeling of being overpowered by the river while either drowning or going over the falls, as people are overpowered by their lives’ flow.

“Twelve Blue” demands patient reading; time must be taken to appreciate the language and figure out how the different story lines relate. I found the story recalls the subtle lyrical style of Faulkner or Ondaatje. True, the meaning doesn’t jump out at you, but that’s what makes it appealing. The challenge of exploring the text and putting the meaning together through snippets of clues enhances the reading experience, and in this case parallels the central theme of human submission to life’s natural flow.

Michael Kinsley offers one reason why newspapers are dying which has nothing to do with cost, technology, or distribution: the wordy conventions of newspaper articles. Kinsley notes that newspaper conventions dictate that the article give “context” and “backstory” whereas Web articles get right to the point. Thus paper articles often give more context than content.

Take, for example, the lead story in The New York Times on Sunday, November 8, 2009, headlined “Sweeping Health Care Plan Passes House.” […]The 1,456-word report begins:

“Handing President Obama a hard-fought victory, the House narrowly approved a sweeping overhaul of the nation’s health care system on Saturday night, advancing legislation that Democrats said could stand as their defining social policy achievement.”

Fewer than half the words in this opening sentence are devoted to saying what happened. If someone saw you reading the paper and asked, “So what’s going on?,” you would not likely begin by saying that President Obama had won a hard-fought victory. You would say, “The House passed health-care reform last night.” And maybe, “It was a close vote.” And just possibly, “There was a kerfuffle about abortion.” You would not likely refer to “a sweeping overhaul of the nation’s health care system,” as if your friend was unaware that health-care reform was going on.

While it’s certainly true that weblog posts tend to be more tightly-worded than newspaper articles, an important factor to remember is that weblogs can be more concise because they link. Rather than giving backstory, we can just link to it. We no longer need to spend several words introducing our source or proving that it’s credible; the reader can easily follow the source and determine its credibility for herself.

Alan Bigelow, writer of several electornic narratives, brings us a new work called “Archetypal Africa,” an interesting blend of video and text. Steve Ersinghaus describes the work beautifully:

"Archetypal Africa" takes a look at common objects in everyday life,and their symbolic resonance within myth and culture. The piece plays with fact and fiction as it leads the user toward an opportunity to define their own archetypal moment.…

Bigelow’s “Brainstrips,” a humorous three-part knowledge series is now presented as a single work (and can also be found in Blackbird, VCU’s online journal).

December 5th marked the launch of Timestamp, a 24 hour networked writing session. Writers included John Cayley, Roderick Coover, Ian Hatcher, Stephanie Strickland and Cynthia Lawson Jaramillo among others. Each artist occupied a four-hour shift, designed to facilitate audiences outside the writer’s time zone.

The event was coordinated in conjunction with Streamflow Conditions, an online exhibition of electronic literature and networked writing curated by Subito Press of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Colorado.

Susan Gibb points to new media professor Dennis Jerz’s screencasts of his 11 year old son, Peter, playing Interactive Fiction for the first time. Familiar with the conventions of modern video games, Peter’s responses and hesitations at the constraints of the IF parser are reminiscent of my own (though perhaps a bit more emphasized due to the awareness of the recording). Though the clips are edited, watching someone new to the genre play through pieces for the first time is enlightening and makes for interesting study.

Interesting to note are Peter’s questions to his father, which are all highly influenced by his experience with other software as he tries to draw correlations to the new form. He asks, “If a word isn’t recognized, can I add it to the dictionary?”

Recently winning the Spike TV Video Game Award (VGA) for Best Independent Game, thatgamecompany’s Flower has proven that the gaming communities, both casual and hardcore, are open to new forms of narrative.

Flower is a downloadable game for the Playstation 3 that allows the player to enter the dreamworld of a flower, breezing through vast fields and beautiful worlds. The game has no fail condition or death; rather than focusing on puzzles or enemies, the developers wanted to focus on the emotional experience of the visuals and movement within the game world.

Flower is available for download on the Playstation network.

Uday Gajendar criticizes today’s gadget-lust, recalling “the truly historically revolutionary game-changers of yore” that included the Memex , Xanadu, Hypercard, and Storyspace .

Gajendar asks why modern technology doesn’t seem to aspire to the cultural and literary significance of its predecessors:

In the end it would be nice if more attention were spent by today’s digerati and nascent auteurs on the groundbreaking things that demonstrate history (writ large, against the canvas of Vannevar, Nelson, HyperCard, SmallTalk, Newton, etc.) and contained the seeds of cultural prominence, lending themselves to worthy criticism, and thus raise the bar for intellectual discourse about modern technological creations.

Of course we’ve all heard the rumors about the Apple Tablet, how it’s going to single-handedly kill the Kindle, and change reading . And now we have some fun speculation about what it might look like.

The creation of imaginary devices is itself an interesting sort of new media. Once, a writer might imagine a chimera; now, they imagine an iSlate.

Jill Walker Rettberg announces two PhD fellowships advertised at the University of Bergen. She notes that Norwegian PhD fellows are entitled to the benefits of university employees:

Norwegian PhD fellowships are renowned for paying as well as a normal job rather than exploiting graduate students: The fellowships are 100% positions with standard Norwegian health, social security and pension benefits (including, say, parental leave, a topic near to my heart these days) and they pay 355,400 kroner (US $55,000/€40,000) a year. You’re an employee, not a student, which gives you far better rights than a student has. You’ll have some travel/research funding assigned to you automatically - I think about 20,000 kroner ($3000/€2200) a year - and the opportunity to apply for more. These are three-year fellowships, where you do about one semester’s worth of coursework (attending conferences and seminars and writing a paper or two) and the rest of the time is reserved for dissertation research and writing. They’re open to applicants from anywhere in the world. You are required to have an MA in a relevant discipline, with a final grade of A (preferred) or B (acceptable if your dissertation proposal is excellent), or equivalent.

The deadline for applications is January 31. Prof. Walker’s recent lecture for Wikipedia Academy Bergen, “Has Wikipedia Grown Up”, is online.

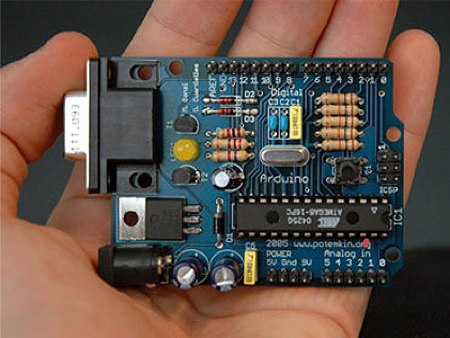

Though it was released in 2005, The Arduino, an open-source robotics prototyping platform, is gaining fresh attention as a means for creating interactive art fixtures.

Arduino can sense the environment by receiving input from a variety of sensors and can affect its surroundings by controlling lights, motors, and other actuators. The microcontroller on the board is programmed using the Arduino programming language (based on Wiring) and the Arduino development environment (based on Processing ). Arduino projects can be stand-alone or they can communicate with software on running on a computer (e.g. Flash, Processing, MaxMSP).

Arduino can be built by hand or purchased preassembled; the software can be downloaded free.

The Arduino takes interactive art projects which were formerly only achievable through teams of designers, programmers, and engineers, and makes it possible for a single artist to install and program a work. Indeed, the accessibility of the Arduino has already led to interesting projects.

Matthew Battles responds to Robert Darnton’s The Case for Books, reminding us that the facets of blogging and social networking that are supposed to be shortening our attention spans—serialization, focusing on small bits of text, jumping from bit to bit—have all been part of the practice of creating commonplace books for centuries.

Deep in the early modern bibliosphere, readers kept notebooks to record especially amusing, provoking, and useful quotations. The resulting commonplace books not only preserved a record of one's reading life, but also furnished material inspiration for further study, contemplation, and writing… [Darnton] declares that early modern readers read "segmentally, by concentrating on small chunks of text and jumping from place to place and jumping from book to book..." does it sound familiar?

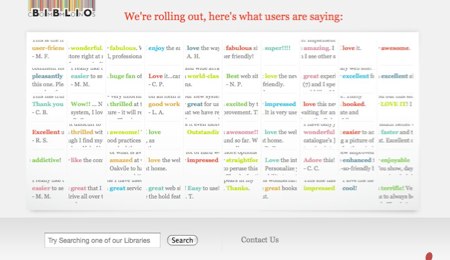

Canadian libraries are taking advantage of social media through BiblioCommons, an online community aimed at users helping each other find the right book. An article by Alex Hutchinson in The Walrus spotlights how the libraries are using the new platform to combat the perception that the library is dying with the book.

Libraries might seem like the proverbial buggy whip makers, doomed to be swept away by changing technology and tastes, along with the outmoded paper books that fill their shelves. But that’s a misreading of their mission: “Libraries were in books because that’s where the information was,” says Kelly Moore, executive director of the Canadian Library Association. “Really, we’re about information.”

I knew that the day would come when I would rather read something on a screen for reasons other than convenience or portability, but I must admit I was not expecting it to be so soon.

The editors of bestseller Not Quite What I Was Planning: Six-Word Memoirs by Writers Famous and Obscure recently released its anticipated sequel, It All Changed in an Instant. The new book features nano-memoirs from Frank McCourt, Wally Lamb, Isabel Allende, and Amy Tan and celebrities like Sarah Silverman, Neil Patrick Harris, and Chelsea Handler.

With Twitter use at all-time highs and growing interests in flash-fiction, the book is appropriately timed, but I found myself genuinely surprised at it’s release in paperback. This actually seems like a book which would be better suited to a screen, and particularly well-suited to something like daily serialization through blogs or Twitter.

We recently discussed the much-debated issue of peer review for computer science conferences. Gene Golovchinsky proposes a new system for rewarding good reviewers in ACM journals and conferences.

I was recently watching a feature-length fanflick video inspired by the Legend of Zelda series. The production value was on par with some of the “dramatic reenactments” I’ve seen on the low-budget History Channel documentaries—good enough that you know what they’re trying to do, but not good enough tto sit in a theater and watch. For a fanflick, it wasn’t bad.

The comments for the movie were mixed, but many of them expressed that the idea of a film adaptation of a movie was doomed because the narrative of a game is too long and dense to be easily compacted into a two-hour film.

And then it occurred to me: Perhaps for the first time, we’re moving into narrative media that are not backwards-compatible. The written word can be spoken, the printed word written, movies can be translated to books, but games and hypertext narrative don’t go backwards.

Or perhaps we just haven’t figured it out yet.

.