June 1, 2010

Stacey Mason

William Hertling, a consumer support strategist for Hewlett Packard, recently gave a talk on “rethinking the link: social jargon.” The talk raises interesting points about linking, wikis, and micro-writing, as Hertling takes advantage of these insights with the new site, AboutUs.com. AboutUs combines a glossary of social jargon with a site for Twitter-sized reviews about other Web sites.

Hertling examines that digital culture has already had a huge impact on writing by making it inclusive and giving more subject background through links. Text messaging has shortened our messages. He predicts that services like AboutUs will accelerate the evolution of language and allow specialized language to be used more freely, as more people will have a concise definition and context for it. He also predicts that as more people are used to having context for words, non-digital reading will become more difficult since you won’t be able to look up words as you go.

May 28, 2010

Stacey Mason

When I recently commented that I wished I’d had an augmented reality program for some of the London walking tours I’d done, I should have know that such programs were already available.

StreetMuseum from the Museum of London uses Google maps and geotagging to show how the streets of London looked in the distant past and provides the kinds of historical facts you might hear on a walking tour.

StreetMuseum is free at the app store.

May 28, 2010

Stacey Mason

The Independent Publisher has released its list of this year’s Independent Publisher Book Awards .

May 26, 2010

Stacey Mason

Alan Bigelow offers an interesting new flash narrative, My Nervous Breakdownl on the nature of sanity and culture.

Upon entering the narrative, the viewer hears the rhythmic cadence of an exhausted march. We’re presented with a top-down view of a brain, with separate sections representing four different areas of the narrative.

The first section I read was the topmost, “What My Therapist Said,” and I expect this is the section with which many people would start. I wasn’t prepared for the sensory overload I received immediately upon entering this area. From an unsettling sound clip of a woman singing—looped playing forward and then backward—to the old, home-movie feel, the therapist’s words were surrounded by a sense of dread. The effect creates an interesting pull away from the background world.

The repetition of the line “my therapist said” suggests both skepticism of the therapist’s authority and detachment from the therapist’s representation of sanity. This detachment is further realized in the section “My Brain Is,” in which repetition of the titular line presents a kind of self-realization and independence from the carnival of the outside world that we experience as background to our thoughts.

My favorite section is “The Metaphor Room,” which consists of soothingly calm, drifting video and invocations of water, floating, and lightness throughout. The text in this section is the most blatant in its invocation of the insane. The section seems to suggest that the only way to be at peace with our insanity is to embrace it. The final section, “How to Dream a Suicide,” echoes this sentiment, as many of the suggestions it offers of clever ways to commit suicide sound more like living than dying.

I found my thoughts returning to this short narrative for several days after I read it.

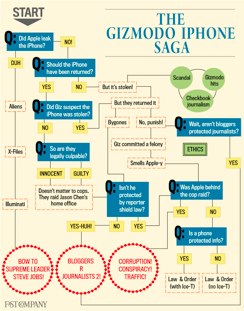

The Apple-Gizmodo saga has certainly raised eyebrows over the last few weeks, and brought up various issues of journalistic integrity. Though a myriad of outlets have covered the story, none have provided a take as amusing as the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure-style hypertext account by Dan Nosowitz.

From the beginning, you can choose to dismiss the whole story as a publicity leak (resulting in a Game Over) or continue listening to hear more.

It’s interesting how the denial of content through the game over mechanic greatly influences your decisions and alignment within the story. This is true of all games to some extent, but a simple shift in which decision constitutes a game over easily sways what the player must think if she wants to continue the narrative.

To be fair, this exists in other forms of media as well—one can always choose to close the book—but the conspicuousness of this decision in games is unique and interesting in its relation to the player-avatar connection.

But don’t take my word for it; Nosowitz offers a straight narrative of the saga for comparison with the hypertext.

Since the days of Dragon’s Lair, gamers have loathed interactive cutscenes and their “press A to not die” mechanic. As narrative structures in games have grown more complex, the feeling has only intensified.

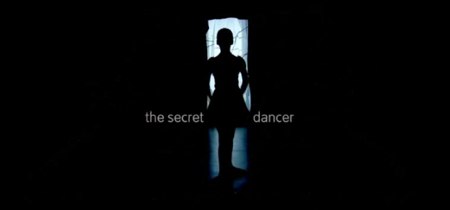

The Secret Dancer was commissioned by the Tate and directed by Martin Percy, is all cutscene. Percy writes that

Tate Kids wanted us to make a file for little girls aged 8-10 which would get them interested in art and in Tate, and which would encourage an active attitude to life. Why they thought that we, slouched permanently in from of out computers, would know anything about an active attitude to life is a mystery, but her, we weren”t complaining.

We created a fairy story around an ancient mythological motif: the statue that comes to life. The statue here is Degas’ Little Dancer, which appeals to our target audience.

Greg Costikyan perfectly articulates why interactive videos feel like a developer’s cop-out and why they do both games and film a disservice.

Now, in part this is a reflection of the fact that "interactive video" is, always has been, and will for all time to come be a stupid idea. True interaction requires multiple paths, the inherently linear nature of filmed video means that algorithmically determined outcomes are infeasible, and therefore we get a branching structure -- which, because of the explosive nature of branching and the high cost of filmed video means that virtually all trees of the branch must be culled. In other words, we end up some a video version of the lamest of choose-your-own-ending books -- a single linear path with "you lose!" cul-de-sacs off to the sides.

It’s interesting to note the influence of technical constraints on narrative content. Game narratives have been struggling to overcome the constraints of their delivery since the very beginning, and while they’ve been improving in their narrative depth, much of the advancement has come through reducing those constraints.

Costikyan also tosses an argument for games as art In Roger Ebert’s direction.

To put it another way, this product, whatever its merits as a film, exhibits an utter ignorance of, indeed a willful contempt for, the techniques of the ars ludorum and the power of the game as a form. If film were the more novel form, I would now, pace Ebert, start to pontificate how film will never be an art, because it cannot match the explorative, variable, challenging character of the game, and every attempt by film to approach the game's strengths in any degree always fails.

May 18, 2010

Stacey Mason

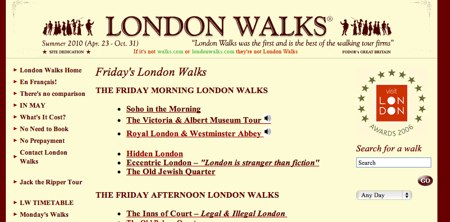

While in London last week for Tinderbox Weekend, I had the pleasure of a couple of walking tours through secret gardens and the familiar haunts of many writing greats. Throughout the tours, the guides asked us to imagine London as it was 300 years ago, and (though I’m a little embarrassed to say so) I found myself wishing for a locative media app more than once so that I really could get the feel for it.

The narrative flow of the tours was interesting, too. I noticed a distinct narrative arc in our guides’ historical accounts. Each stop of the tour would begin with the necessary dates, flow into a story—often with a gossipy and speculative tale, give way to what history is known for sure, and then offer a tantalizing hint about the next tour stop. Because of this, each stop felt distinctly like a book chapter.

There is also something to be said for locative narrative during these tours. Aware of Brian Greenspan’s work on the subject, Mark Bernstein and I both commented on how interesting a locative narrative would be in London’s narrow, winding streets.

May 17, 2010

Stacey Mason

After a trip overseas and an adventure of a homeward journey, Eastgate has returned from Tinderbox Weekend London.

Robert Brook, who works for UK’s Parliament, spoke on using spatial hypertext in meetings to facilitate discussion. A Tinderbox map has the advantage over slides or completed charts of giving the audience the feeling of an ongoing process. Few presenters would pause their presentation halfway through to change a slide to incorporate the audience’s ideas, and they certainly wouldn’t do it more than once.

Brook described how the screen acts as a mediator, abstracting ideas by moving the discussion from “you” versus “me” to a third party, making meetings and discussions less confrontational. This way, no single voice dominates the meeting and nobody feels overpowered.

Michael Bywater gave us a fascinating look at his use of Tinderbox as he writes a musical. A musical obeys constraints that don’t exist in other forms: you have a a limited cast, a finite production budget, and characters burst into song from time to time. The chorus provides a ready pool of minor characters, but the same actor can’t be in two places (or two costumes) at the same time. Two hundred horses can’t blaze across the stage. Smoke can’t rise from the treacle pudding.

And on top of all of this, they sing. And more precisely, they have to sing when the dramatic tension has reached such a point that they can’t do anything else.

It’s a lot to keep track of.

Tinderbox helps sort it all out by keeping track of who is where at which times, as well as plotting the dramatic tension of a given scene. By assigning a numerical value value on a 1-10 scale, Bywater’s Tinderbox can literally plot the dramatic tension of the scenes, acts, and whole musical to make sure that the intended dramatic curve is achieved.

May 14, 2010

Stacey Mason

Roger Ebert recently argued that games can never be art, partly because of the player’s need to win. I have doubts about this, and the issue was recently brought up again this weekend as I watched some friends play the World of Warcraft board game .

I’m certainly not arguing that WoW is art in any way beyond the stunning talent required to produce the visual beauty of the world . But here you have a game that one doesn’t win. There are objectives and goals, but there is no win condition.

Does this mean WoW is not a game? Perhaps. It’s been argued to be many things, and often even argued (and indeed experienced by many of its players) to be work.

What fascinated me, however, was the adaptation of this computer game in which there is no winner into a board game in which there is. Of course, it’s not difficult to impose some arbitrary goal, but the real fascination came from the change in the atmosphere of the game simply by adding a victory. Now there was a sense of competition, but more importantly, there was an ending.

As with any cross-media adaptation, the change in the system of constraints created a unique and interesting approach to an experience that tries to be as similar as possible to the original. So how did the board game handle those constraints? Their conspicuousness delighted players through their ability to remain fairly true to the mechanics and balance of the original. The narrative of the game, however, got lost in the brilliance of the mechanics.

The ludology vs narratology debate continues.

May 12, 2010

Stacey Mason

Amidst Orwellian arguments on the degradation of written language in the digital age, a strange brand of tweeper emerges.

A small but vocal subculture has emerged on Twitter of grammar and taste vigilantes who spend their time policing other people’s tweets — celebrities and nobodies alike. These are people who build their own algorithms to sniff out Twitter messages that are distasteful to them — tweets with typos or flawed grammar, or written in ALLCAPS — and then send scolding notes to the offenders. They see themselves as the guardians of an emerging behavior code: Twetiquette. (NY Times)

I’m not entirely sure this classifies as the internet using its powers for good. It kind of just seems like some stranger telling you to keep your elbows off the table while you’re at the local pub with your friends. After all, even Homer nods.

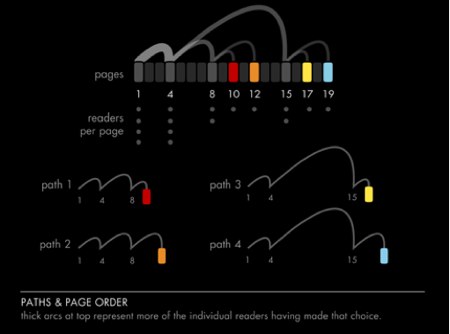

Wireframes discusses Christian Swinehart’s visualization of Choose Your Own Adventure books and relates the diagrams to design practice:

What if readers of our deliverables were guided through a set of predefined flows? What if the flows we design required readers to make choices in order to achieve multiple endings? On one end of the extreme spectrum we have passive documents such as wireframe decks where there is often a single thread of experience. Here we have guidance, but no choice as we flip from the first page till the end. On the other hand of the spectrum, we might have a fully interactive prototype. Here we have zero guidance and tons of choice (perhaps even too much). Could this more balanced combination of guidance and choice then be a more powerful means of conveying interaction and narrative in our field?

After pondering this conflict between of choice versus guidance, it occurs to me that digital narrative has been striving for the artifice of choice, knowing fully well that this artifice exists. It is not possible to give choice completely to the reader, a fact which has been discussed at length in the eLit community.

Technical constraint, artfully masked as narrative constraints, offer comfort and guidance to readers. The dungeon master exists for a reason, though the ideal story seems to require his infrequent, invisible guidance.

After enjoying growing success over the past couple of years, it’s almost time for a fresh 100 Days Project with Steve Ersinghaus, John Timmons, Carianne Mack Garside and the gang .

Timmons will lead off this year, creating a short film each day for 100 days from which all the other artists will draw inspiration. The crew hopes that this year will be even bigger than last year’s impressive turnout. The quality of many of these pieces is astounding, especially considering how difficult it is to churn out original creative work every day for 100 days.

100 Days 2010 kicks off on May 22.

.