Clutching at Straws is an online poetry journal that features “strange, head-scratching, absurd, and hilarious” poetry. The poetry is, well, strange. The site tends to feature peculiar—or sometimes non-existent—metrical patterns. I hold such poems to a higher standard of lyricism, since the poet needn’t deal with the constraint (or the safety net, depending on your viewpoint) of simple meter.

Still, much of the poetry is funny, and some is successfully thought-provoking. I have yet to find a poem that is musically beautiful, but that doesn’t seem to be the site’s goal. It’s great for an afternoon chuckle or head-scratch.

MIT Professor Nick Montfort has announced the launch of his new digital narrative authoring system, Curveship. The system models not only the fictional world and its characters, but the narrative discourse as well; it can rearrange the story events or structure responses from a specific character's viewpoint.

Montfort explains,

I hope the system will be useful for teaching about narrative theory and for research in AI, computational creativity, and related areas. But its primary purpose has always been the creation of new types of electronic literature.

Curveship is built using Python and is currently free to download

Gatsby

Stacey Mason

Office productivity everywhere has come to a grinding halt this week with the sudden popularity of The Great Gatsby, a Flash adaptation of a mysterious NES game.

The game plays more or less like your typical NES platformer, except that you are Nick Carraway. You begin at Gatsby's party, where you must dodge pestering butlers and raucous partygoers to find the host. The game features several NES-style cutscenes with dialogue taken directly from the book.

Blogging the Humanities

Stacey Mason

The Online Education Database recently published a list of the 50 best blogs for humanities scholarship. Most of the literature blogs listed are in fact, the literature sections of online newspapers and magazines. However, these do serve as good springboards to other sources, and there are a few independent literary blogs listed.

There are also several very interesting weblogs for other disciplines including philosophy blog Think Tonk , Games With Words – a linguistics blog concerned with the connection between words and cognition, and the edgy art blog Juxtapoz .

Microsoft Narrative

Stacey Mason

Microsoft Research has buit a new system for creating and experiencing "Rich Interactive Narrative," built on top of their Silverlight browser plugin. The system aims to provide a richer multimedia experience, allowing for both a reading and authoring environment.

So far, most of the examples are enhanced video experiences. They seem to offer video with deep-level zooming and annotation. I didn’t find these particularly deeply engaging from a narrative perspective, but can easily envision future works with more diegetic complexity.

ELO Literature Collection V2

Stacey Mason

The ELO has released it’s Electronic Literature Collection Vol 2, including familiar titles like Mateas and Stern‘s game Façade and Rettberg, Gillespie, Stratton and Marquardt’s The Unknown, as well as many works that were new to me.

Following Jill Walker Rettberg’s resolution to read more eLit, I’m going to make a solid effort at doing the same. This is a fine starting point for discovering new works and authors.

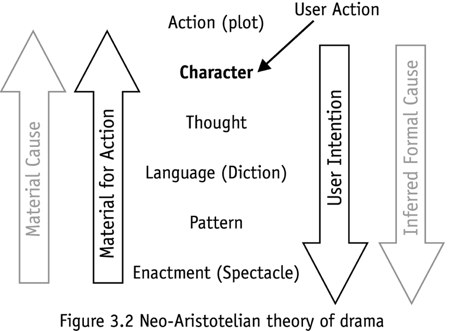

Recent interest around Eastgate in the role of agency in narrative immersion has led me to a fascinating essay by Michael Mateas, co-author of Façade. Using Aristotle’s theory of drama as a starting point, Mateas diagrams the role of agency in interactive drama, adding an additional model of choice and causation atop Aristotle’s diagram of narrative causation. This addition results in the proposition that “a player will experience agency when there is a balance between material and formal constraints.”

Leaning heavily on previous work by Murray and others, the essay provides and interesting perspective for anyone interested in agency and its relation to interactive narrative.

Atavist

Stacey Mason

Practical and economic constraints of the publishing industry have long placed restrictions on the length—and thus to some extent the content—of novels. As the industry has grown more digital, people began to ask why we still had to stick to the same industry standards. We don’t have to worry about how thick a book’s bindling can, or what the production costs and shipping costs will amount to.

An electronic book should cost less to manufacture than a print book, but what, exactly, is the value of content? Some would argue we’ve never charged for content. Many readers and authors have called for more freedom in the length and content of works that should no longer be restricted by these economic concerns.

The economics of bookstores also set a lower bound. Shorter works – individual stories, lectures, broadsides, and songs – that sold well in the 17th and 18th centuries became difficult to sell in the 20th and vanished from bookstores. Enterprises from Amazon Kindle Singles to Murdoch”s The Daily are exploring this boundary.

The Atavist is an answer to that call, an app for Kindle and iPad that considers itself a boutique publisher of digital literature . Atavista is releasing works at $2.99 for a work that runs roughly 12,000 words (and will soon be releasing them for $1.99 on the Kindle and eventually Android). It offers an unobtrusive back-channel of multimedia content, and considers itself a hybrid between books and magazines.