Rutgers Assistant Professor Christina Dunbar-Hesterr shares the syllabus for her PhD-level course on technology and new media. The course offers an introduction to the idea of technology and how it shapes society. Posting her syllabus online and explaining how each reading and assignment relates to the next gives the course a narrative framework and allows other instructors to learn from the way she structures the course.

Web founder Sir Tim Berners-Lee has called for opposition to Hollywood-backed proposals to allow US Courts to censor internet traffic.

The Observer has published an interesting debate on whether video games or film best depict the realities of war. Of course, the point that Migual Sicart almost makes is that games have the ability to affect the player through an intimate player-avatar relationship that doesn’t exist in movies.

Does that make them better? Debates like this irk me. If someone asked me whether theater or cinema was the superior medium for conveying the realities of love, I would be no more able to provide an answer. Games are good at forcing the player to recognize things about themselves and abstract concept through their own identification with a situation. Movies are good at eliciting empathetic reaction and allowing a greater level of observation.

Neither is better than the other. We should stop trying to apply artificial superlatives to narrative media.

Web Art Science is an unconference for people who do hypertext. London, November 6. Organized by J. Nathan Mathias (Emberlight), David Millard (Southampton), and Paul De Bra (Hypertext 2011 Conference Chair).

Digital: A Love Story is a free downloadable interactive narrative by Christine Love. Its interface has a quaint late-80s feel—appropriate for the 1988 setting—which certainly got some confused looks on the subway as my shiny MacBook was running an archaic system. The work invites the user to traverse the story by dialing into BBSs, reading messages, and downloading new applications to the in-story desktop.

Despite what my subway neighbors were thinking about the dial-in modem noises,within minutes I was living my childhood fantasy of hacking into mainframes and corresponding with other hackers. The narrative invites you to choose a screen name for yourself, and I admit that at first I gave myself a generic name. However, after about 3 messages, I changed it to something that sounded more screen-name-appropriate, only to change it to something that sounded more like a cool hacker later. It was on-par with the difficulty of choosing a gaming handle, perhaps because I have always equated the two. I was so into the story-world that I wanted my name to say something about me and project an image the same way that I would for an online video game.

And through the course of the narrative, I made friends and enemies, though I’m sure it had nothing to do with my screen name. But I don’t want to give too much away, since discovering the story is really the fun part.

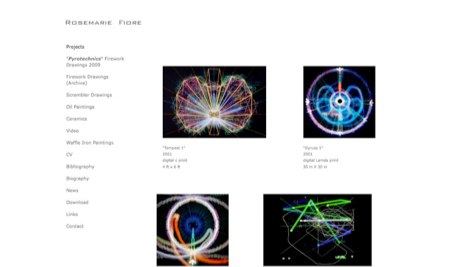

Rosemarie Fiore has created colorful works of art by taking long exposures of video game screen grabs as she played.

Brad Reiss used a similar technique in World of Warcraft to not only create beautiful images, but also to study player behavior within the game. The long-exposure images revealed not only how much information a player must process in short amounts of time, but also demonstrated interesting patterns of player travel within cities and idiosyncratic player habits.

For those of you that have been keeping your eye on The Mongoliad, the new serial fiction from Neal Stephenson and Greg Bear, new information has appeared at last.

The narrative is set in 13th century Foreworld, a universe very much like our own, and will be released in weekly installments with annual or semi-annual subscription fee. Premium subscribers will receive extra bits of art, video, and music, and the story will be available through mobile platforms. Stephenson and Bear invite readers to expand the story through the site’s forum and wiki. Interesting ideas will be added to the official canon.

The Mongoliad sounds like an interesting dive into multi-media linked storytelling, but the execution is going to be critical. Currently, the chapter texts exist separately from the media extras; the reader is presented a menu from which she can choose to view the text or the illustrations . On one hand, this format allows for immersion into the text without the distraction of the other media. On the other hand, clever integration would allow for a richer reading experience, and we’re all pretty accustomed to illustration.

It’s still too early to tell if the project is going to be a great success or an interesting footnote, but either way it’s worth following.

The Oxford English Dictionary probably will not print its next edition on paper. The Oxford University Press noted that a print edition would not be ruled out should demand prove sufficient. But with the third edition still more than a decade away, it will probably only be available in electronic form.

The OED pioneered research in hypertext and electronic books, and many features that are common today (or widely wished-for) in the iPad, Kindle, and other eBook readers were originally proposed in the research of Raymond, Tompa, and their colleagues at the Centre for the New Oxford English Dictionary

Nigel Portwood, the chief executive of Oxford University Press, estimates that printed dictionaries have a shelf- ife of another 30 years.

Rudi Seitz, the creator of Quadrivial Quandary , offers Pictorial Matter, a word-challenge site that looks to engage creativity through associations of image and language.

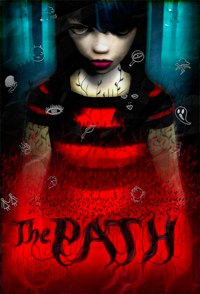

Susan Gibb points us to an article on the creation of The Path, a retelling of Little Red Riding Hood that navigated the difficult waters of a the commercial “art game.” Gibb notes that a central issue the article raises is one that has plagued hypertext since Coover’s famous 1992 New York Times article on the End of Books: does the artist write for the community most likely to understand and appreciate it, or does she concentrate on “breaking into” an untapped mass audience?

At the very start of the project, we weren’t really sure if The Path was going to be a commercial title or a more artistic experiment. As we continued to refine the design, we realized that the concept had several things that spoke in favor of commercial exploitation. It was going to be a horror game, thus easy to categorize by the market (unlike 8 for which the main problem with publishers was that its genre was undefinable.) In The Path, we knew we were going to have stylish, dark, girl characters at a time where gothic Lolita style, and Pop Surrealism was very trendy. Cult rock star Jarboe had agreed to do the sound track. But most of all, we felt a sort of obligation, to at least try and make this step towards a market, instead of safely playing in the margins. Up until the day of launch, we had no idea how well this was going to work. But we decided to take the risk.

In addition to a look at the concepts, decisions, and production that went into creating The Path, the article also points to a gallery of “beautiful glitches” that arose in designing and testing.

Joining my discussion with Stephanie Boluk, Patrick LeMieux offers an exhibit on the art game, looking at how these games fit into a broader scope of art history.

The installation draws upon the work of Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and Ad Reinhardt, among others. LeMieux has implement various interactive features that limit (thus highlighting) certain gameplay features and how they relate to the classic artist’s work.

By limiting or removing critical elements of classic gameplay (e.g. top-down mazes that repeat endlessly, side-scrolling shooters without enemies) and by adding the avatars and actions of post-expressionist artists (e.g. Stella, Warhol, Reinhardt, Rauschenberg, Klein) the severely repressive aspects of both gaming and artmaking emerge as infinite loops. Along with the games, an open source library of critical writing allows viewers to browse, pirate, remix, and input texts in the gallery. The main focus of this work is to address the act of interpretation within gaming, modernist painting, minimalist sculpture, and art criticism.

Last Spring, Eastgate dropped into Leancamp, an unconference for young startups who subscribe to lean business principles. The conference was a sea of Mac-toting 20-something males in jeans and sports jackets. The buzzwords of the day were “lean,” “agile,” “collaborative,” “cloud,” “social,” and all of the other familiar words of today’s internet businesses. All of this more or less met my expectations, though I I was surprised by the gender imbalance.

The unexpected part came from talking with people about what they are looking for in software. Everyone wanted collaboration, sharing, and all of the social media virtues. But within this microcosm, there seems to be little room for the individual. People scoff at client-side software designed for individuals. As we’ve seen in social media, everyone contributes but no one is heard.

The question has been bouncing around electronic literature for years, Is our emphasis shifting from the single author to teams? Is the idea of the artist obsolete? Is it ridiculous to expect an individual to create a brilliant work? Collaboration is interesting, but it can run the risk of reducing art (and software) to a mess or a mob. It often takes an individual to reinvent the way the everyone thinks.

During the Future of Digital Studies Conference, Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux gave a paper on eccentric games. Mark Bernstein asked whether these eccentric games were avant-garde. Boluk answered that she thought that calling these games avant-garde was problematic, and in fact their paper had been careful to avoid the term.

I asked her to unpack this idea. The term “avant-garde” has been slowly creeping into gaming circles (even commercial ones) as a way of expressing unusual gameplay styles, so why the distinction?

She writes,

It's such a loaded term that opens up a huge can of worms and is riddled with strange paradoxes (e.g. how do you have a radically original artifact function as a model within a conceptual tradition without destroying its originality?). I don't pretend to be an expert, but the avant-garde is often associated with the idea of a conflation of art and life (contrasting the autonomous art object), a historical period (e.g Dadaism or Surrealism), a philosophical condition (the concept of originality), or a generalist definition of avant-garde as some sort of oppositional position.

To take the avant-garde in these broad strokes and apply it to my work with Patrick, I don't think the games we discussed really make sense within an art historical tradition (it'd be a stretch to compare them aesthetically or ideologically with Dadaism for example) and they don't really work philosophically as "new" or "original" since they elaborate and build upon past traditions and games. […] This referentiality makes it hard for these games to fit into the concept of the avant-garde as a revolt against tradition. In fact, the games we discuss emphasize their connection to past gaming genres (like the references to Donkey Kong, Mario, and the history of the platforming genre in Braid ).

If the game world is quick to correlate the new, different, or innovative games with the avant-garde, I think the popularity of “art-games” like Flower, Passage, and The Path is to blame. These games challenge the the fundamental ideas of mainstream gameplay such as the supposition that games must have a challenging but achievable goal and that the player's interaction with the gameworld has direct consequences on the game's outcome.

But what does all of this have to do with a new work on zombies?

Boluk is currently putting together a serious anthology on zombies from critical, theoretical, and historical approaches. Suggested topics range from “Zombies and Spectatorship” and “Queering The Zombie” to “The zombie as political allegory”. Is it the idea of the automaton zombie as it relates to the automaton machine? Surely that gets very interesting if you consider a game like Portal which is an eccentric game and whose villain is a sentient machine (if such a machine exists).

They were definitely conceived as independent projects coming out of very different interests. […] This games project deals with a certain kind of aesthetic of morbidity (Lazzarini's skulls is a really important model for us as a kind of ontology of digital media which references traditional anamorphosis as memento mori). Some of the works we looked at (e.g. Braid) are also dealing with a post-atomic landscapes in the same way many zombie texts are working through similar post-atomic anxiety. Patrick has talked a lot about the relationship between digital media, art history and atomic anxiety in another essay he wrote about JODI , Magritte and Foucault. I think your point about the machinic subjectivity of the zombie is also a good one; I know, for example, many zombie critics actually use Haraway's “Cyborg Manifesto” as a point of reference.

But I think that the more obvious connection is my dissertation on seriality. It's something that came up in in our presentation with the discussion of cursor*10 and meta-gaming activities such as mass-AI simulators and tool assisted speed runs. There's something very striking to us about visualizing what was once individualized, anomistic and repetitious activity in these scenes of collectivity. The serial nature of the zombie is something that is similarly striking to me.

.