HTLit spent the weekend at MIT for the second international Web Art Science Camp, Dangerous Readings.

We weren’t entirely sure what to expect, and initially tried to closely model E-LitCamp. However, the group was very active and participatory, and the space was very good for fostering more informal discussion. Influenced by Alan Dix’s description of Tiree Tech Wave, it soon became clear that enforcing a session structure would only dissuade productive conversations.

The weekend opened with Bill Bly’s excellent presentation of We Descend Volume 2, which set the tone for interesting discussion that continued through the weekend. Bly’s demo confirmed that hypertext literature has indeed come a long way from the StorySpace works of old, while still embodying the very essence of hypertext literature. The text, like the first volume, is very much exploratory, and the spatial relationships of the interface encouraged an excellent discussion of authorial process—should form follow content or vice versa?—that became a recurrent theme throughout the weekend. It also raised questions of what should be shown to the reader, which bits of text are reserved for the author’s personal notes; if hypertext affords some overlap, how does it shape the work?

MIT’s Angela Chang demoed an interactive iPad narrative for children that encourages parent-child reading and interaction. The work met much adoration from the group, and spawned an interesting of how interactive narratives and interfaces encourage different reading and thought patterns, particularly in young children. Chang explained that children were able to recognize a relationship between text and meaning from a much younger age while engaging with the work.

Jonathan Brandl and Nick Apostolides starred in a dramatic reading of Mark Bernstein’s hyperdrama The Trojan Girls, an interesting spin on The Trojan Women that takes place in the not-so-distant future during the second American Civil War. The work argues that hypertextual recombination of dramatic dialogue can yield identical plots while changing other facets of the text (adding subtext, changing inter-character relations, etc). A fruitful discussion followed the reading, which examined the nature of reordering plot events and the relationship of constraints and narrative building.

Remix aesthetics and cross-media adaptation were recurring themes of discussion, seen in informal presentations of Meanwhile for iOS, Steve Meilleux’s 100 Days work, and The Trojan Girls. A reader takes a unique pleasure in recognizing familiar elements in a remixed work—discovering and recognizing implicit links—and there was much discussion over how much an understanding of context adds to a work. Other recurring themes included publishing models, sources for new work, the role of the institution in fostering creation, the value of criticism, and anticipating reader experience in the writing process.

The weekend was very successful and, personally, very helpful for clarifying and focusing ideas for future research. Huge thanks to Eastgate and MIT’s Comparative Media Studies and Writing and Humanistic Studies programs for sponsoring what was ultimately a very productive and engaging weekend.

Twitter archives are available, as is a trip report by Andrew Plotkin.

Nick Briz, a Chicago-based tech artists discusses the aesthetics of JODI’s glitch art:

There are few conceptual artists whose work illicit the same response years after it’s production, JODI want people to see their work (and read their emails) and be caught off guard, be confused, upset, scared, ecstatic, and never comfortable about technology.

It’s probably easiest to view JODI’s work through a Cagean or dada-lens, and while that’s a valid (and often appropriate) perspective to take, personally I’ve become more interested in the way work like JODI’s questions and/or calls attention to our relationship with digital technologies. A point of tension we can’t ever seem to get over within the “arts” (and society at large) is whether technology is inherently good or evil, whether it will augment reality or destroy humanity. The truth is technology isn’t inherently anything.

Lee Rourke tells us why creative writing is better with a pen. Surprise: it’s not the smell of paper! Rourke argues for writing with a pen, MOVING beyond the standard stationery fetish, and he’s not alone in his preference.

"Pen and paper is always to hand," agrees Jon McGregor. "An idea or phrase can be grabbed and worked at while it's fresh. Writing on the page stays on the page, with its scribbles and rewrites and long arrows suggesting a sentence or paragraph be moved, and can be looked over and reconsidered. Writing on the screen is far more ephemeral – a sentence deleted can't be reconsidered. Also, you know, the internet."

The real message should simply be “write.” It doesn’t matter if you dress it up in fancy paper or bang it out on a screen.

Just write.

MLA 2012 will host an Electronic Literature Exhibit, curated by Dene Grigar, Lori Emerson, and Kathi Inman Berens. From the exhibit website:

Because the ultimate goal is to present electronic literature in a way that makes it understandable to non-practitioners and scholars new to it, we have chosen to organize the work, first, by medium—desktop, mobile, and readings and performances—and, second, by approach and style, like locative, multimodal, and literary games, instead of genres, such as hypertext fiction or flash poetry, etc., usually associated with electronic literature.

This statement makes an interesting supposition about genre in eLit, namely that it is a relatively unchanging—a bold assumption in such a young field, but one that is made frequently. If our genres aren’t based on approach and style, what are they based on?

Perhaps it may useful to look to other artistic forms. Genre is a shorthand for the reader to understand how to approach a work. If we separate art into content and delivery—terms which do not exactly correspond with the narratologists’ fabula and sujet, but are more concerned with subject and form respectively—we see that different media take different approaches to classifying genre. Music focuses almost entirely on delivery and formal issues, especially within popular music. The lyrics to a song make no difference to which genre the song belongs, hence why artists of different genres cover the same song, altering the delivery to fit the constraints of their own genre.

Film and books are a bit more complicated. If an alien appears in your story, no matter how it’s framed, it’s a good bet your story will be shelved in sci-fi; thus, we have a case for genre being content-controlled. However, genres also have established formal conventions: we expect more extreme long shots in epic battle films than in romantic comedies. We expect that biographies will have a certain discursive structure and tone. Moreover, delivery and formal treatment might push a film from a drama to a comedy through a complex combination of fabula and sujet. Genres blur together, and edge-cases are easy to find.

What about video games? The gaming industry has established genres based on interaction method. An action-adventure game and a first-person-shooter might have the same story, items, enemies, protagonist, and tone. The genre is completely defined by delivery, though certain genres tend to keep to similar content.

Most eLit researchers (including the exhibit curators) have defined eLit genres in terms of the genres proposed by Katherine Hayles in Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary . Hayles outlines several genres of eLit: hypertext fiction, network fiction, locative narratives, installation pieces, codework, generative art, and Flash poem. Again, we see a focus on interaction method (delivery) over content, regardless of fabula or sujet.

. Hayles outlines several genres of eLit: hypertext fiction, network fiction, locative narratives, installation pieces, codework, generative art, and Flash poem. Again, we see a focus on interaction method (delivery) over content, regardless of fabula or sujet.

Genres are indeed a useful shorthand for discussion, however we shouldn’t feel constrained by them. Platform-specific demarcation, while useful and well-conceived in the context of the exhibit, is not plausible for serious academic discourse. Some forms, such as interactive fiction, have clear conventions and expectations. More nebulous corners of eLit, like the catch-all “digital poetry,” might benefit from the definition of clearer poetics and critical practices before we corral ourselves into genres.

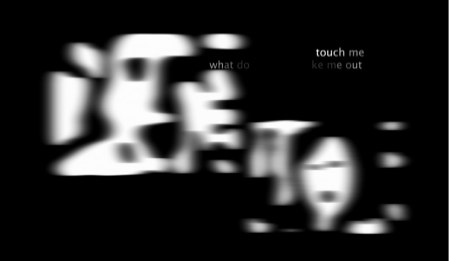

Christine Wilks’s Out of Touch is an exploration into the detachment and superficiality of virtual interaction through video poetry reminiscent of the Expressionists. The piece opens with a black screen, ambient typing noise, and inviting phrases that the reader will recognize from various social networking platforms. As text appears and disappears, the nebulous background coalesces into two ghostly images, faces reduced to abstractions.

The audio, video and starkness of the piece serve the mood very well, imparting feelings of loneliness and uncanny horror. Brian Kim Stefans’s assessment that there are “echoes of The Scream” in this piece is certainly founded. The ghastly monochrome visuals evoke feelings of detachment, curiosity, and repulsion that are all a part of the online experience.

The lines of text often complement the other media well, but the places where they don’t are too numerous to ignore. I’m reading this with acute awareness of the postmodern, and the aesthetics that generative works have contributed to digital poetry, but I grow tired of the poets—presumably caught up in the quest to combine words in new ways—forcing the reader to decipher or impose meaning onto nonsensical phrases.

Some lines are clear and resonant: “Do I mean anything to you?” But these are often overshadowed by cryptic lines like “You’re too touchy typey” or “Dream me texts” that are grammatically on par with generative poetry. The words themselves are not sufficiently emotionally charged, not effective forms of rhetorical devices, and not presented in such a musical rhythm as to excuse the lack of clarity. There are many arguments for why these lines might work—fractured language symbolic of fractured relationships, a reflection of online communication, it’s fashionable in digital poetry—but the piece does not gain anything from such grammatically fractured lines that couldn’t have also been achieved through clearer language.

Still, the visuals are powerful, and the work as a whole successfully explores loneliness and the fetish (and artifice) of human connectedness inherent in social media, a theme to which many of us can relate.

When I first read Jason Shiga’s Meanwhile, I thought it was a clever idea. Though I thought the form would have been easier to follow on a computer screen, I recognized that much of the charm came from the fact that it wasn’t. Still, when I found out that Andrew Plotkin was working on an iOS implementation, I was excited to see how the adaptation compared to the codex version.

Interacting with the narrative on the iPad feels very natural. All of the story’s panels are contained in a single sprawling map. The current panel illuminates while the rest of the map darkens around it. Tapping on the panel moves you to the next panel or decision. At any time, the reader can select to browse the entire map, and can select any panel to begin the story from there.

The background doesn’t darken very much, so distraction and temptation from other panels is constant. At first I took objection. Surely, the digital platform allowed the author to force the reader to follow the panels as they were intended. But the distraction of possibilities of alternate pages and panels is also present in the original; at any time, a reader can flip to a new page and start the story from there. In that respect, the fact that the reader is free to explore the entire map is a deliberate release of control that could have been more rigidly enforced by the author or implementor—a good decision in keeping with the spirit of the original codex. Where the book controled how visible the consequences of choices were by hiding them on another page, the iPad interface analogously hides consequences with zooming when necessary. My only complaint is that I think the legibility might benefit from the map being more closely-zoomed by default. This problem is easily fixed with pinch zoom, but moving to the next panel automatically resumes the default zoom level.

Zooming issues aside, Meanwhile uses Scott McCloud’s idea of the infinite canvas to good effect. McCloud points out that the space-as-time metaphor can be better used digital comics because authors can make temporally distant events also physically distant without the fear of wasting paper. The narrative of alternate timelines benefits from the events being laid out on the same screen to give the whole work a feel of simultaneity.

There are few funny hypertexts. Is comic writing really that hard? Steve Almond weighs in on writing funny.

The comic impulse is, in essence, a form of radicalism, an attempt to subvert the predictable bromides of our superegos. It's the force that propels well-behaved little Philip Roth from the comfy suburban confines of "Goodbye, Columbus" to the libidinal jungle of "Portnoy's Complaint." It's what allows Aristophanes (or, for that matter, Jon Stewart) to express moral outrage without moralizing.

The reason young writers have so much trouble "writing funny" is because they are so often dead-set on appearing serious. They view any trace of mirth in their prose as proof of their frivolity, a judgment that critics tend to ratify.

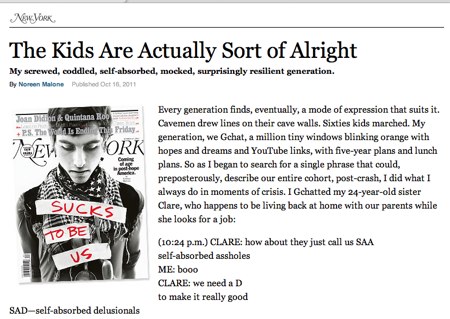

Though clearly written in a pre-9/11 bubble of optimism, David Brooks’s idea of The Organization Kid has been particularly resonant in a recent revival of generation wars. So what happened to the hyperachieving students, those energetic meritocratic elite? Many of them became disillusioned 20-somethings. And somewhere underneath this tired, we-have-it-worse generation war, there’s a question of the role of the institution.

American universities are good at churning out walking resumes, but isn’t the role of academe to teach students how to question, how to think critically, how to analyze? Should universities be expected to undertake such issues of character building? Or is this the natural byproduct of letting everyone into the sparkling pearly gates of College with promises of middle-class security on the other side?

Game theorist Tom Chatfield and Second Life creator Rob Humble discuss how to engage players within virtual worlds.

Humble believes the secret to sustainable virtual worlds is meaningful user-created content and interaction “so that [users] are not waiting for developers to be making all the content.” World of Warcraft would disagree, and seems to have succeeded through precisely the model Humble denounces. What both models share is a system that fosters interpersonal relationships and constructs social models and hierarchies within that system. Both feature currency to reward invested time, but currency also translates into in-game goods that pander to our desire for social status and the admiration of our peers.

The discussion reminds us of social facets of virtual worlds, but does little to address engagement beyond mirroring real life and making it more rewarding. Is it possible to create engaging, personalized narratives for each player, all interweaving and coming together to form a larger story with different points of view? How do we do this while preserving a sense of agency for the player?

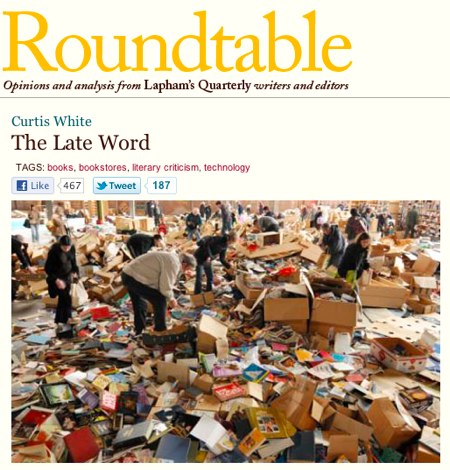

Dept. of the End Of Books

Writing in Lapham’s Quartrerly, Chris White offers a thoughtful and educated approach to the perils that the publishing world faces—and more importantly, how these perils will affect the existing ideal of “literature” and the crowning of its next generation. He writes,

When we speak of literature, we should not imagine that we are speaking of some stable and enduring Platonic entity. The history of literature has always been about its highly mutable institutions, whether bookstores, publishers, schools of criticism, or, for the last half century, the mass media. In other words, literature has always been about the struggle over who would have the social authority to determine what would count as literature. Early on, this authority seems to have been the possession of men who had the privilege of owning printing presses and bookstores. In our own time, the most compelling claim to this authority comes either from the capacious bosom of Oprah Winfrey and her bathetic book club, or from the arid speculations of those Hollow Men on a publisher’s marketing staff.

White doesn’t subscribe to the “books are doomed” cliché, and he doesn’t idolize the small, independent bookstore; which he remembers as nothing more than a few disappointing tables of bestsellers surrounded by decorative bookshelves and served by employees who didn’t read. White disputes the idea of content and of the book as a platform, and likes to jab at “content providers” and “the techno-hip” to little purpose. But his concern lies in the idea of the bookseller as an usher of taste, seeing large bookstores, mass media, and internet culture as having the ability to control the institution of “literature.”

Criticism and recommendation are the points at which his arguments become contradictory. He focuses on the power of the publisher and seller to influence the idea of what is “literature” (and therefore what is “good”) and on the power of the internet to influence the masses, but doesn’t reconcile the competing ideals of literature as a high-brow endeavor beyond bathetic pop-culture recommendations.

Now, through word of mouth and blog site recommendations, some will find that book of poetry, although those folk will be, I suspect, mostly poets themselves, reduced now to a rarified species of hobbyist no greater in number than those enthusiasts who attend quilting fairs. (In all honesty, this is already a done deal.) But the population of people interested in finding that transforming book will become ever smaller. Literature requires a culture, a book culture, and the ebook and the web, for all of their wizardry, will forever be solipsistic.

Beyond this contraction, White has painted himself into a corner with the idea that taste is an institutional product. Though he doesn’t acknowledge it directly, academia is responsible for the very idea of literature that White wants to protect. The intellectual elite shape literature into anthologies, archives, theories, and syllabi, naturally preserving the notion of “literature” and assigning merit to work they have collected while damning rejected work to be dismissed or—worse—forgotten.

So at the end of the day, how do we find the good work? Everything relies on thoughtful review. We need more well-written, thoughtful criticism. And in the eLit world, first we need more writing.

.