Late news from the decline of books and booksellers:

- Paul Duguid, “Do You Love Books?” (TLS) reviews Bonnet’s

The Phantoms On The Bookshelves, Horowitz’s

Publishing As A Vocation, and Thompson’s

Merchants Of Culture.

- Nicole Kraus, “Writer’s Block: the end of bookstores” (The New Republic)

- Jessa Crispin, “A Sea of Words” (Smart Set) has the subtitle, “Publishing isn't dead. Smart publishing, well, that's a different story.’ She begins:

“In the week it takes me to read five different books on how to be a writer, approximately 30 books are delivered to my Berlin apartment. This is a decline from the 15 to 30 that used to be delivered every day, and I’m grateful for the barrier of costly international postage that keeps these numbers down. I will immediately discard about three-quarters of the books. Some of these, I would say maybe eight percent of the books I receive, are self-published. Under their bios the writers dutifully list the writing programs they attended. Now they have landed here, with a clip-art book cover, a cheap binding, and a $12 stamp to send it to a book critic who doesn’t even really review fiction anymore. I feel bad for these writers, and the years of effort and money they spent on a writing education, and all of that boundless optimism that had to be required to get to this point. I do not, however, feel bad enough to read their books.”

- Ben Ehrenreich, “Death of the Book” (LA Review of Books)

- Bill Keller, “Let’s Ban Books”, is an editor at the NY Times and wishes his employees would stop asking for quite so much time off to write books.

“I’ve learned interesting things from the books of my staffers. I learned that I employed a financial writer who got himself so deep in debt he couldn't make his mortgage payments, a media columnist who had been a crack addict and a restaurant critic with a history of eating disorders. (To those who found these cases problematic, I replied that there is no better qualification for writing about life in all its complexity than having lived it.)”

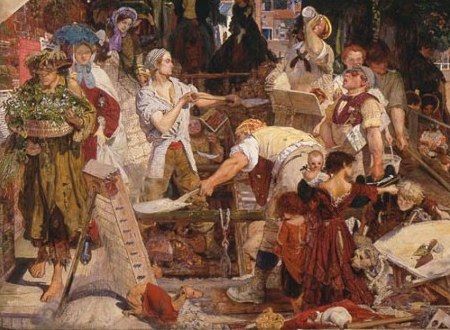

Ford Maddox Brown, Work (detail), Manchester Art Gallery

Lorie Emerson tweets, “Hypertext is the new realism,” a reflection that deserves some thought. Hypertext has long been associated with postmodernism, and occasionally with modernism, but realism has never really crossed my mind. It’s an interesting claim, one that probably needs clarification in a field of mixed ontologies and contended vocabularies.

First, what do we mean by “hypertext?” HTLit (and our sponsor Eastgate Systems) takes a broad view of “hypertext,” encompassing any kind of linked structures or interactive work. Links don’t have to be underlined blue bits of text; they are evident through a reaction within the work that is triggered not just by clicking, but by any interaction that the author specifies should cause something to happen. However, the idea of “hypertext fiction” put forth by Kate Hayles in Electronic Literature is probably more widely used within the field. She breaks electronic literature into “genres,” distinguishing “hypertext fiction” for its lack of sound, image, and video as the “first generation” or “classical” works, (echoing Coover’s Golden Age) thereby limiting the scope of what “hypertext literature” actually includes.

By “realism” I assume we’re talking about the 19th century artistic movement that focused on capturing an objective truth. But how is hypertext (either as a subset of eLit or as an encompassing entity) realism or something like it?

If we limit the scope of hypertext to Hayles’ definition, many of these pieces were direct in their representation of the structure of the work. Readers could see the entirety of a work’s structure more clearly than is possible in interactive fiction, for example. However, this is not true for all of them, especially once we started viewing hypertext work on the Web. Likewise, if we’re interested in visual aesthetics of hypertext pages and their stripped-down appearance, surely IF is a closer fit, especially works like Dan Dan Shiovitz’s Bad Machine, though arguably their awareness of this fact puts them more in line with moderism or postmoderism.

In visual art, the practice of realism was influenced by the camera, a revolutionary technology affording new artistic possibilities and in turn influencing aesthetic sensibilities. Camera’s could produce images that seemed to captured the objective truth. Perhaps like the camera, hypertext has not only acted as a new technology that allows for innovative forms of electronic literature, but it has also changed our sense of what makes a work of eLit good. Surely, though, every artistic movement has faced similar changes in critical practice, and technology has always shaped art.

If we limit the scope of “realism” to literature, the search for the objective truth manifested a focus on gritty realistic depictions of life and hardship. Hypertext is perhaps analogous, as it reflects intricacies of connectivity that have become more and more foregrounded in 21st century life. If moderism’s stream of consciousness is a romantic impression of the mind at work, perhaps hypertext’s fragmented and sporadic paths and its dead ends are the reality of the contemporary experience, a gritty representation to overtake that romantic ideal.

We might have come to a new objective truth here, except that many of these works actually deemphasize the idea of an objective reality. Instead, they highlight the fact that truth, meaning, and interpretation of experience are created by context; the reader imposes them onto the artistic vessel. Although hypertext may seek to capture a “realistic” view of connectivity and intertwingledness, its heart still lies with postmodernist relativism.

In The New Republic, Jed Perl takes a close look at Thomas Kinkade: Artist In The Mall (Alexis Boylan, ed.)

(Alexis Boylan, ed.)

“A number of contributors cannot resist the temptation to take Clement Greenberg’s old essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” for another spin. I find this absurd. What on earth does a piece of writing that was meant to explain the miracle of Picasso, Braque, and Mondrian have to tell us about the work of a man who, though undoubtedly full of himself and his achievement, is mostly out to make a buck?”

Perl doesn’t think much of Kinkade’s paintings, filled with nostalgia for an imaginary past in which everyone lived in a Main Street USA where it was always a nice Spring Sunday and everybody would soon be heading to church with armfuls of flowers from their family gardens. Neither, it seems, do the contributors to this academic volume, who seem to fly to theory as a defense against the banality of their subject.

Perl’s real target, however, is not Kinkade but the enterprise of academic media critique.

This sort of self-aggrandizing pseudo intellectual discourse puts me in mind of Edmund Wilson’s unforgettable attack on pedantry in the English departments, “The Fruits of the MLA,” in which he bemoaned—way back in 1968—“the indiscriminate greed for this literary garbage on the part of the universities.” The only thing that really distinguishes the new greed for garbage from the old is that garbage has itself become so chic. In the Kinkade anthology one finds garbage embraced with both guilelessness and aggressive high-camp cheers.

For the last six days, I have visited the Museum of Modern Art to try to get a glimpse of Marina Abramović as she sits in her chair for “The Artist is Present.” Or rather I’ve been playing Pippin Barr’s virtual interpretation of the experience. The verisimilitude is brilliant—or excrutiating—I’m not quite sure which. Maybe both.

You walk in to the Museum of Modern Art –assuming, that it, that you sat down to play the game during the hours when the real museum is open. The game is on a clock set to New York time, and if the real MoMA is closed, you can’t get in.

Once inside, you purchase a ticket and give it to Security. You stroll past a few famous pieces like van Gogh’s “Starry Night” and Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans.” Then you hit the line somewhere around Matisse, so you wait...and wait...and wait some more.

At this point, you might be tempted to go do something else or tab to another site. If you do, and the line shifts, the person behind you will get frustrated with you and you’ll get pushed out of line. And there’s no cutting either, no way to reclaim your spot once you’re pushed out. Depending when you start, you might wait for hours. At 5:30 EST, the museum closes and you’re booted onto the street.

The game demonstrates how important user experience is to gaming, not just to ensure that the player is enjoying herself, but also in understanding games as an emotional vehicle. This game is boring, and when you get to the end, it’s underwhelming. However, the boredom and the stoic ending give the player plenty of time to impose her own thoughts and interpretations onto the game, which actually captures the spirit of the exhibit, and postmodern art as a whole.

Alan Jacobs revisits the legacy of Marshall McLuhan :

I have been reading McLuhan off and on since, at age sixteen, I bought a copy of The Gutenberg Galaxy. His centenary — McLuhan was born in Edmonton, Alberta on July 21, 1911 — provides an occasion for me to clarify my own oscillating responses to his work and his reputation. I have come to certain conclusions. First, that McLuhan never made arguments, only assertions. Second, that those assertions are usually wrong, and when they are not wrong they are highly debatable. Third, that McLuhan had an uncanny instinct for reading and quoting scholarly books that would become field-defining classics. Fourth, that McLuhan’s determination to bring the vast resources of humanistic scholarship to bear upon the analysis of new media is an astonishingly fruitful one, and an example to be followed. And finally, that once one has absorbed that example there is no need to read anything that McLuhan ever wrote.

Jacobs is the author of the intriguing The Pleasures of Reading in An Age of Distraction , which sets off from a critical but not entirely unsympathetic reading of Mortimer Adler, whose fascination with Great Books and popular treatise on How To Read A Book

, which sets off from a critical but not entirely unsympathetic reading of Mortimer Adler, whose fascination with Great Books and popular treatise on How To Read A Book are the very incarnation of middlebrow. Neoconservative Adler and Neoliberal McLuhan are interesting bookends to the study of new media, though on bad days one might think that New Media pundits have too readily mixed McLuhan’s polemics with Adler’s reactionary conservatism.

are the very incarnation of middlebrow. Neoconservative Adler and Neoliberal McLuhan are interesting bookends to the study of new media, though on bad days one might think that New Media pundits have too readily mixed McLuhan’s polemics with Adler’s reactionary conservatism.

The Electronic Literature Organization celebrated its move to MIT Monday night with its Open Mic/Open Mouse event. Several prominent digital authors turned up to read their work, as well as some very promising student authors. John Cayley demonstrated a version of his speaking clock. Fox Harrell presented his Loss, Undersea project as well as bits from his Living Liberia Fabric project.

Eastgate author Robert Kendall presented his poem Faith, published in the Electronic Literature Collection Volume 1, which features an interesting application of stretchtext using color, animation, and sound. He also premiered a followup work that looks promising but which is only partially completed.

Aimee Harrison presented a a digital poem with audio and video accompaniment. Though I’ve complained in the past about video illustration, this was not the awkward videos of the vook, and the verse itself was good. Starting with hypochondria and dealing with issues of sanity and perceived health, the images of medical tests that look for neurological disorders were creepy and disquieting.

Samantha Gorman—who will be reading at a Purple Blurb event later this fall—read from an interesting poem that explores the idea of the machine as a coauthor. With a methodology reminiscent of John Cayley’s presentation at the Future of Digital Studies conference last year, Gorman translated an original poem from English to Spanish using Google translator, then translated the piece back to English. The resulting poem, though changed in wording and (in many ways) also in meaning, still held a certain metric beauty and metaphorical meaning. It’s an exercise that probably wouldn’t work with prose, but because a reader approaches poetry with the expectation of metaphorical and lyrical language, the result was convincing.

The open mic platform is an interesting idea for digital literature, and it worked well. I wonder if the format would work as well with more game-focused works like Every Day the Same Dream that focus on agency, discovery, and frustration. ’m generally a fan of showcasing IF through readings even though it offers a completely different experience from actually playing the work. Overall, the event went well and I look forward to another season of Purple Blurb events.

Bournemouth University Media School has announced its second annual new media writing prize, available to both students and professionals. The winning student will receive a laptop computer; the overall winner will receive an iPad. Bournemouth University acquires a perpetual non-exclusive license to the winning works.

Deadline for entry is October 31st. Digital publishers and press will be on hand at the Awards ceremony on November 23rd.

Eastgate is issuing a call for projects for an upcoming creative hackday, Web camp and unconference that we’re calling Dangerous Readings.

Dangerous Readings is designed to be a small, informal gathering of artists, computer scientists, and researchers. It will be an "unconference:" the participants will set the agenda. The focus will be project sharing, cooperation, and creation. We're welcoming hands-on technical projects, novel digital literature or literary systems, or any other digital art projects or research. We especially want to hear about new work and work in progress. Students are welcome and encouraged.

Dangerous Readings will take place November 19-20 in Boston. If you’re interested in participating, please contact Stacey Mason at smason [at] eastgate (dot) com.

Contre Jour references Angry Birds and other popular mobile games.

Contre Jour, Mokus’s recent multitouch game for iOS, offers an interesting new spin on the casual mobile game. Winning Best Handheld or Mobile Game nomination at E3, Contre Jour combines gameplay elements of Angry Birds, Cut the Rope, and World of Goo with beautiful noir art design. A hauntingly beautiful soundtrack by David Ari Leon recalls Yann Tiersen’s work on Braid. In fact almost everything from this game can be traced to another game, a fact about which many app store reviewers have complained.

So if Contre Jour doesn’t offer novelty, why would it garner so much acclaim? The easy answer is because it’s fun and beautiful, but the game does offer clever allusions to its predecessors, often with tongue in cheek. It wants to be compared to other mobile platformers, either for parody or to showcase the brilliant art elements of the game.

What Contre Jour really offers is an exercise in tone and mood, while perhaps commenting on the state of mobile platforming games. The bittersweet soundtrack combines with dark, monochromatic levels to give the work a much more serious tone than other Chillingo titles. The opening credits reveal that our genre-appropriate cutesy circular protagonist, Petit, is a reference to Le petit prince, which also clearly inspired certain terrain textures, background art, and the world selection screen. Even the title, French for “against daylight” and a reference to the contre-jour artistic style, suggests a deeper theme than “Angry Birds” or “World of Goo.” But even with all its efforts to offer an artistic experience, Contre Jour manages not to to take itself too seriously. It’s still fun .

Phone Story is an “educational game” by Molleindustria for iOS that follows the manufacture of the iPhone around the world, depicting violent and inhumane work conditions in its production. From the Phone Story Web page:

Phone Story is a game for smartphone devices that attempts to provoke a critical reflection on its own technological platform. Under the shiny surface of our electronic gadgets, behind its polished interface, hides the product of a troubling supply chain that stretches across the globe. Phone Story represents this process with four educational games that make the player symbolically complicit in coltan extraction in Congo, outsourced labor in China, e-waste in Pakistan and gadget consumerism in the West.

Keep Phone Story on your device as a reminder of your impact. All of the revenues raised go directly to workers' organizations and other non-profits that are working to stop the horrors represented in the game.

The game was banned from the app store two hours after its release, with Apple citing “excessively objectionable or crude content” and “[depiction of] violence or abuse of children” as well as objections to the ability to make donations to charities, which is only permitted in a free app.

Without being able to play, it’s difficult to assess on the quality of Phone Story as a political game. Super Columbine Massacre, for example, had an interesting political message that took advantage of agency and the player-avatar relationship to connect players to the protagonist. It would be interesting to see if and how Phone Story uses this relationship to convey their political message. This may be something we see more of in the future.

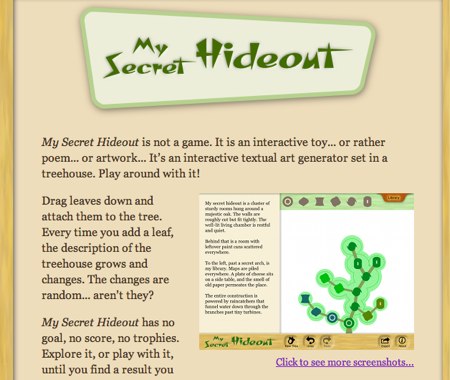

My Secret Hideout is a new iPad app by renowned IF creator Andrew Plotkin. The user uses the touchscreen to move various node shapes onto a tree interface, with each addition creating or lengthening one of the trees branches. As the user adds nodes, the prose in the text pane changes with additional details about a secret hideout. The user is free to move nodes or even whole branches after they are placed, and the prose will still change accordingly.

Em Short wrote a thoughtful critique of the work. She muses on how we might categorize a piece like this.

This isn’t in any meaningful sense a game: there aren’t any goals, scores, win/loss states, etc., and it’s hard even to see how one might project such things onto the structure.

It’s also not a story. I’ve often argued for the power of setting as a story-telling mechanism, and the significance of objects as conveyors of narrative, My Secret Hideout doesn’t entirely respond to that kind of treatment. The descriptions are too flexible, the whole output too mutable and dreamlike[…]

To the extent it is a toy, the toy-nature is about figuring out how it does what it does and how much agency you can reasonably exercise over the output.

My Secret Hideout is the generative prose version of a sandbox “game” like Minecraft, where the focus is on creating and changing a world. But that’s not an all-encompassing description. “Toy” is probably the most apt: it promotes play and encourages the interactor to push the boundaries of the system, to experiment with combinations not because we are particularly interested in the changing output, but because we want to understand how that output is being created. Once we understand it, we can then play with our decisions to craft the prose, or draw aesthetically pleasing trees, as we see fit.

My interaction with Hideout reminded me very much of my experience with ToneMatrix. As I approached the piece I made random decisions to try to figure out how the system was interpreting my inputs, then used that understanding to create artistic pieces within the app’s framework. My Favorite Hideout has a library in which you can save your creations.

Judy Malloy, its name was Penelope, edition for iPad, in press

As Eastgate begins to focus on making its collections available for mobile devices, I find myself musing on the idea of a digital publisher. What is the publisher’s role?

Publishers of the past provided the capital to make literature available to the masses, but today anyone can self-publish. In a market with such low barriers to entry, however, writers have a difficult time finding their audience, and publishers serve as marketers and, through selective branding, as crtics.

So if the publisher’s job is now to point our audience to best eLit, we need categories for judging electronic literature. Mark Bernstein pointed out this problem (as well as the changing role of the publisher) in his 2010 paper “Criticism.” In the paper, Bernstein explores a number of ways we have tried to judge eLit in the past demonstrating the flaws in each approach. What Bernstein doesn’t explain is how we should critique eLit.

One approach may be to go back to Ulmer’s ideas on electracy. In order to understand eLit as a form that incorporates many types of media, we must be literate (electrate) with those types of media, understanding their critical practices and how to interact with these technologies. If a work includes audio or film, surely a working knowledge of music and film theories are essential to a deep analysis of the work. With various works combining different media in different ways, a one-size-fits-all approach can’t work; you can’t analyze afternoon in the same way you analyze Alan Bigelow’s Web yarns. But understanding the individual components of a work, and how they fit together to create the theme, mood, tone, etc. of a piece is a step in the right direction.

(Writing for myself only)

Perhaps prompted by the ELO’s recent call for eLit syllabi, Porter Olsen at the University of Maryland posted the syllabus for “Literature in a Wired World.” The course looks great!

Have your own syllabus? We’d love to share it!

Haruki Murakami (A Wild Sheep Chase, Norwegian Wood) reminds us that talent is nothing without focus and drive. It’s not enough to be talented, you have to actually do the work. (Thanks, @BookBench)

.