In promoting his latest collection of short stories, For My Next Illusion I Will Use Wings, Alex Epstein released the work on Facebook, using text in photos to tell the stories.

I deliberately chose the very low-tech format of a photo album, trying to keep the focus on the stories themselves (but also knowing that Facebook would offer better exposure to a photo than to text). This also made the book readable not only on a computer but also on an iPad or a smartphone, and even by people that don’t have a Facebook profile, without almost any technical effort on my part.

This experiment is interesting, but it led me to wonder what a whole fictional account might look like. Sure, Facebook itself has already showcased one when debuting the Timeline feature, but only to tell a typical life story. What might the steampunk version look like? Or the hard-boiled mystery version? The story could be told over a whole network of Facebook Timelines, and the prominence of visual art, video, and outside links in the piece could make for something like an interlinked digital comic.

Has anyone done this yet?

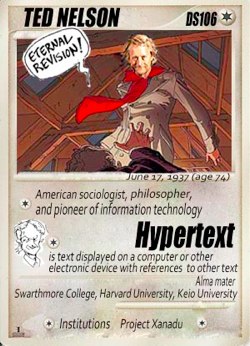

The internet delivers another round of brilliant remediation in the form of the Ted Nelson Pioneer Pokemon Card. The card was made by Yue on what appears to be a student website. The site also contains posts on Alan Kay, Douglas Engelbart, and J.C.R. Licklider, and we hope more Pokemon cards will come.

Clint Hocking explores why interactive dialogue is so bad: it’s because we’re holding it to the standards of film.

Functionally, film dialogue must never say anything that is visually apparent. This is what the cinematic axiom ‘show don’t tell’ means. But game dialogue is different. Game dialogue is a form of feedback, and as feedback, its very purpose is to clearly indicate that a game state has changed. In the case of the guard, his line of dialogue is a clear indicator that he has detected a sound, but has not visually acquired the player and that he is about to begin a dangerous search behaviour. No reaction shot required.

So, really, when we say game dialogue is terrible what we’re really saying is that it simply does not sound the way our cultural expectations tell us it should sound. In a sense, it is like saying radio writing is bad writing. Of course radio writing is bad writing… for film.

The funny thing is that I’ve never actually thought that game dialogue was bad (poor translations notwithstanding). Of course, it’s repetitive; that repetition is a signal to the player that she got all of the information that character could offer. Most players will repeatedly speak to the same character until they get to the repetitive part.

Works that experiment with forms of dialogue, like Facade, Alabaster, or Prom Week, are fascinating, but we need to understand the aesthetics we’re striving for—and departing from—in order to get the most out of them.

Ewan Morrison asks whether self-publishing is the next bubble, of the magnitude of the dotcom bubble or the housing bubble, and if so, how does that play out for the publishing market?

Meanwhile the mainstream publishing houses have suffered huge losses and now can only publish authors who seem to offer a guaranteed return. The entire field of publishing has shrunk, beneath what seemed on the surface like an infinite expansion. Publishers have been forced to launch their own epublishing sites in the attempt to join in the bubble and gain kudos, but they are too late and are wasting resources, and further undermine their old status as market leaders. They in fact turn to the new model of the self-epublishing "star" to get them out of the doldrums. This is the point at which self-epublishing becomes a hall of mirrors and speculation runs in circles.

And what has happened to all those new authors who were told they could make money from epublishing? Well, they are working entirely for free (on spec) on the promise of those big 70% royalties on future sales. They write their books, they blog, they net-network and self-promote; they could put in as much as a year's work, all without payment. So much writing-for-free is going on that it upsets the previous paradigm: people start to ask, why should any writers get paid at all? Why should "professional" writers get a wage or advance, when I've had to do all this work on my self-published ebook for free?

A recent Reddit post, which targets women who fake their “nerdiness” for male approval, has launched the internet into polarized opinions on what it means to be a nerd and to have nerd cred. The post features a busty woman saying “I own over 50 X-Men comics! I’m a total geek!” and a male responding with a dismissive, page-long rant.

No—no you’re not.

You’re just a sad girl who at some point let a marketing campaign convince her that “geeky” was vogue and having spent the 10 years since high school graduation desperately scrambling to amalgamate the idiosyncrasies and opinions of others into an ineffectual Franken-avatar to stand guard at the gates to the maddeningly black abyss that should house the unique personality that you never bothered to cultivate, you were more than willing to adopt this paradigm—watered down as it may be—for use as a sort of Cliff’s Notes to the person that you aren’t.

And it goes on, in similarly verbose, self-important prose until it comes to a sexist joke at the end.

As I mentioned in a recent post, nerd culture is not particularly female friendly. But the backlash from the sexist attitudes—the more frequent feminist posts on popular gaming blogs, the increased attention to women in games—shows that women are really getting tired of being told they can’t be in the club.

At Tinderbox Weekend in San Francisco, I met Neil LaChapelle, who is working on an app to engage and foster budding cultural scenes. LaChapelle introduced me to the idea of “scenius,” a term coined by Brian Eno to capture the idea that genius and creation are often surrounded by a culture of freely-flowing ideas. LaChapelle has done research on cultural scenes, and he gave me a brief template for the life-cycle of a scene. It turns out, not surprisingly, that gaming culture (and nerd culture if you view them as two distinct cultures) has followed the model pretty closely, and is now beginning to see a very typical backlash, one that was also experienced by the 80s punk scene, the 90s grunge scene, Harry Potter fandom, and is even reflected in sports fandoms as a team goes through its highs and lows.

The lifecycle of a culture goes something like this:

In the beginning, there is a spark of nebulous cohesion, people bonding over a shared value or idea. Often, this is nothing more than a reaction to a shared problem. As more people join the cause, the group’s goals start to coalesce. The group recognizes common traits or interest as points of shared identity. Eventually, a budding scene comes together around a central figure, place, or event, with those common interests now serving as the focus of “cred” to show that one belongs to that scene.

With the stabilization around a central focus, the scene expands, becomes more public, and more appealing to outsiders. As the scene becomes flooded with new members, many original members cling to the idea of cred and see the increased popularity of the culture with disdain. The culture becoming increasingly “mainstream” is a source for contention between members, and the increasing number of members leads to new ideologies within the group. At this point, the group may disintegrate and disperse, or a section might break off and establish a counter-culture.

Sound familiar?

Gamers I knew were first excited then fiercely angered when popular stores like Hot Topic started selling video game T-shirts, once a very public badge of cred within the community (see also this black shirt with a smarmy sentence in white letters) but now a symbol of “gamer” as mainstream ideal. The casual revolution was a further slap in the face to “hardcore” gamers, who saw the type of male-centric console gaming that they were doing as superior to the moms playing the Wii. Somehow the hardcore scale also coincidentally settled along a corresponding “masculine scale” with highly masculine console games getting the most cred, fantasy/RPGs somewhere in the middle, and casual games at the bottom. And if you aren’t hardcore enough, you can’t call yourself a gamer. Especially if you’re a girl.

Now that attitude is getting resistance in the gaming community, particularly from women who are tired of men assuming they don’t belong. It’s possible that we’re starting to see the rise of a counter-culture that values feminist ideals, challenges the idea of masculinity as the foundation of gaming cred, and rejects stereotypes that seem be getting worse, not better. It’s a counter-culture that I support and hope to help foster into the new age of gaming culture.

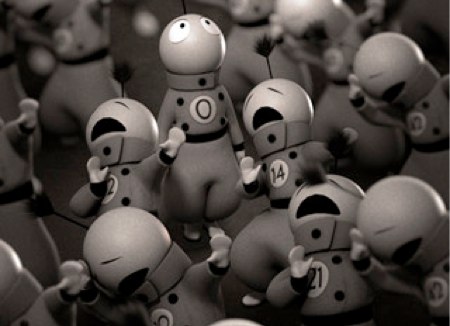

After being very impressed with Moonbot's The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, I couldn't resist picking up their adorable follow-up, The Numberlys. The story follows five numberlys (pronounced "number-lees") as they strive to bring letters (and by extension colors and fun in general) to a grey world that names everything with numbers. The numberlys even talk to each other in numbers, a clever audio trick that is translated by the text and voiceover. Sci-fi fans will appreciate homages to Metropolis and Flash Gordon.

The opening cut scenes are long. So long, in fact that the first interactive point came just as I was thinking this was not an interactive piece at all, but a short video, and was considering the possibilities of what that meant for content delivery economic models. Once the interactive cuts start appearing though, they are actually more numerous and more interesting than the ones in Morris Lessmore. The puzzles might be a little difficult for children, as the interaction is not always intuitive, but it's clear that Moonbot is heading in the right direction in terms of how they combine interactivity with storytelling.

My only real complaint with the work is the choice of the German stereotyped accent for the voiceover. It's unfortunate, especially as it describes a dystopian society that views everything with zealous efficiency and reduces its citizens to numbers. It's possible that this was an oversight and the accent was chosen to get in pronunciation jokes (like "Z End"), but either way it was not done in good taste.

Still, the work shows all the polish in appearance and score that we saw in Morris Lessmore, and Moonbot is positioning itself to become the Pixar of the app store.

Since my first encounter with vooks, I’ve been skeptical. Is this as far as the big-budget content developers are willing to push the medium? I’m using the term broadly to cover not just Vooks® but any digital narrative with a shallow, lackluster interpretation of how video and text can combine to tell a story. I’m talking about a platform that bills itself as the future of reading but actually amounts to little more than ebooks with video illustrations.

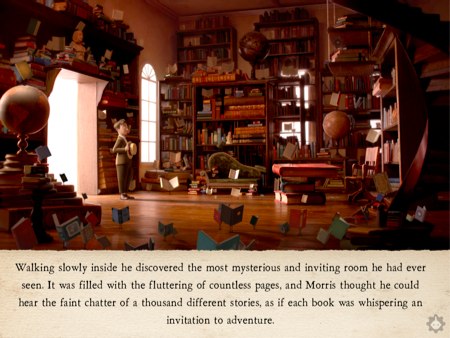

Then I found Moonbot’s The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.

I admit, with some embarrassment, that the idea of children’s vooks had occurred to me, but only as a passing thought. I had seen the work Angela Chang is doing with the iPad, which still makes vooks seem unambitious and unoriginal. But in truth, there really is nothing wrong with a picture book, especially if it’s beautifully executed.

Morris Lessmore is a very beautiful children’s book with wonderful voiceover, fantastic scoring, and breathtaking video clips. There are a few interaction gimmicks, touch things to make something small happen, but the lack of substance in the interactions is overshadowed by the polish and care that has gone into the work. And not all of the interactions are shallow: one page gives a young reader an opportunity to play the piano, and gives adults a preview of the interactive lessons that might be more thickly interweaved into children’s books in the future.

.