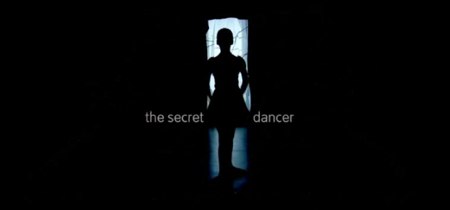

Secret Dancer

Since the days of Dragon’s Lair, gamers have loathed interactive cutscenes and their “press A to not die” mechanic. As narrative structures in games have grown more complex, the feeling has only intensified.

The Secret Dancer was commissioned by the Tate and directed by Martin Percy, is all cutscene. Percy writes that

Tate Kids wanted us to make a file for little girls aged 8-10 which would get them interested in art and in Tate, and which would encourage an active attitude to life. Why they thought that we, slouched permanently in from of out computers, would know anything about an active attitude to life is a mystery, but her, we weren”t complaining.

We created a fairy story around an ancient mythological motif: the statue that comes to life. The statue here is Degas’ Little Dancer, which appeals to our target audience.

Greg Costikyan perfectly articulates why interactive videos feel like a developer’s cop-out and why they do both games and film a disservice.

Now, in part this is a reflection of the fact that "interactive video" is, always has been, and will for all time to come be a stupid idea. True interaction requires multiple paths, the inherently linear nature of filmed video means that algorithmically determined outcomes are infeasible, and therefore we get a branching structure -- which, because of the explosive nature of branching and the high cost of filmed video means that virtually all trees of the branch must be culled. In other words, we end up some a video version of the lamest of choose-your-own-ending books -- a single linear path with "you lose!" cul-de-sacs off to the sides.

It’s interesting to note the influence of technical constraints on narrative content. Game narratives have been struggling to overcome the constraints of their delivery since the very beginning, and while they’ve been improving in their narrative depth, much of the advancement has come through reducing those constraints.

Costikyan also tosses an argument for games as art In Roger Ebert’s direction.

To put it another way, this product, whatever its merits as a film, exhibits an utter ignorance of, indeed a willful contempt for, the techniques of the ars ludorum and the power of the game as a form. If film were the more novel form, I would now, pace Ebert, start to pontificate how film will never be an art, because it cannot match the explorative, variable, challenging character of the game, and every attempt by film to approach the game's strengths in any degree always fails.