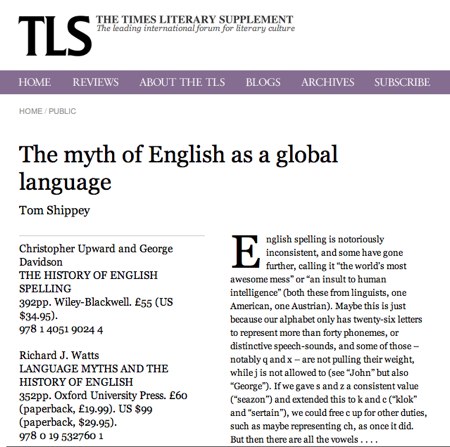

Myth Of A Global Language

Mark Bernstein

In “The Myth of English as a Global Language,” Tom Shippey traces the origin of common myths and pernicious metaphors of the evolution of the English language, many of which can be traced to nationalism, classism, and mistranslations over the centuries.

The dangerous one as regards English, I would suggest, is language as threatened female, whose “purity” is continually being “violated” or “polluted” by vulgarisms, Americanisms, anything one doesn’t happen to like. If one pursued this image, one would have to say that English, far from being a pure maiden, looks like a woman who has appeared out of some distant fen, had more partners than Moll Flanders, learned a lot in the process, and is now running a house of negotiable affection near an international airport. But metaphors can be taken too far.

The witty piece offers sound arguments on why our language has evolved as it has, and how its continuing evolution affects our social structure.

The real and serious issue must be the use of Standard English, and Standard American, to “strengthen social elitism and exclusion” in the present time, and here there are two views. To speak personally, I was once present at a lecture urging the use of “Ebonics” (African American Vernacular English) as a teaching medium in predominantly black American schools. At the end of the lecture an African American stood up and said, in Standard American, that he was a lawyer specializing in defending African Americans in the courts; and that if he did this in AAVE rather than Standard American, his acquittal rate would be much lower. So, stick to one’s principles, and see young men sent to jail? Lament the prejudice which creates such a situation, and do nothing? Or accept bidialectalism? It’s easy for linguists – writing, of course, in perfect Standard English, or else they wouldn’t get published – to take the high moral line.